Similarly we, as players of Dead Men, are dishonourable and murderous. Kane is a cad and a killer, but he isn’t penalised or rewarded for that behaviour in any overt way – no matter which way he goes in the end, the results will be horribly mixed. The clipped, uncomplicated writing in Kane and Lynch: Dead Men (we always arrive at scenes at the latest possible point, leave them as quickly as possible) prevents the game devolving into any sort of moralising. He isn’t doing bad things in order to eventually do good ones, nor is he a whipping post for the audience – an easy villain, a hate figure. Nothing Kane does has any narrative sway or significance. It’s this distinguishable lack of catharsis and pay-off – this disinterest in script-writing standards – that makes Dead Men one of the only games that is truly about bad guys, truly about violence. But Shelley and Rific die anyway, Jenny gets shot during the rescue and Dead Men nevertheless ends on a blunt down note, with Lynch, Kane and his lifeless daughter floating down a darkened river in a stolen boat, towards nothing. It would undo his betrayal years earlier in Venezuela, give his character a traceable arc and reward the player with a Good Ending. Typically, selecting and carrying through that second option would be a moment of absolution for Kane. Conversely, at the end of Dead Men, you’re presented the choice of either boarding a helicopter with Kane’s rescued daughter, Jenny, or returning to the firefight in an attempt to rescue Shelley and Rific, two of the criminals duped into accepting the Cuba job. If during one of the game’s many gunfights you shoot a civilian, nothing happens – no pop-up warning, no remarks from Kane, Lynch or any of the other crew-members. He is, as the other characters constantly assert, a “fucking traitor.”īut Dead Men isn’t interested, at all, in judging Kane. Kane really did betray his colleagues and run out with the money. “It’s bullshit,” Kane protests, and normally in videogames, where bad guy characters and their histories are simply misunderstood, he’d be telling the truth. He’s accused throughout the game of pulling a similar trick on another job – allegedly, he abandoned a group of mercenaries during a firefight in Venezuela, and kept whatever loot they had captured all for himself. When the whole thing goes awry, and the gang is pinned down by gunfire, Kane exclaims “fuck the men,” and leaves them to die.

Kane and lynch 2 dog days boosting cracker#

In that early bank robbery mission, when the escape van crashes and the two eponymous criminals come spilling out of the back, Kane takes one look at the driver and the safe cracker who were sat in the front seat and says “leave them.” Later, he lies to his partners in crime, claiming he’ll pay them if they come on a job to locate his kidnapped daughter. He possesses a trait which is largely absent from videogame protagonists: selfishness. But it’s actually Kane who stands out in Dead Men.

Kane and lynch 2 dog days boosting full#

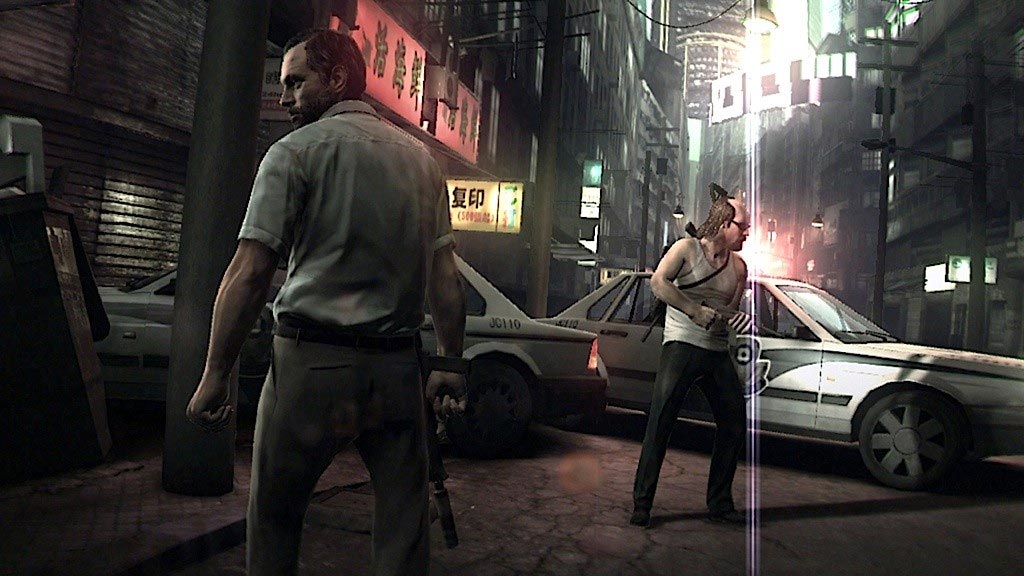

In a discussion about gaming’s playable villains, Lynch, the schizophrenic who murders a bank lobby full of hostages seems like the character to gravitate towards. That’s why a game like Kane and Lynch: Dead Men is so impressive, and so valuable. The anti-hero, rather than the true villain – the true Unreliable Narrator – reigns because he’s easier to explain. “If you go here and do this you’ll save somebody’s life” is an easier thing to communicate than “go here and do this, because it’s what your character would do.” And in videogame writing, brevity is king. Writers seem concerned that the people who play games won’t connect to characters – won’t interact with a game’s systems and objectives – if the motivation they’re given is “negative.” Saving the world, or at least, saving something, is a better vector for player engagement. True “bad guys” are mostly missing from games. Jackie Estacado is avenging his dead girlfriend, and destroying a New York mafia family in the process. John Marston is trying to save his family, while at the same time battling the formation of a new, corrupt Federal government. Likewise, the leading men in titles like Red Dead Redemption and The Darkness, although they’re violent and dangerous, are each striving towards some kind of objective, grander-than-themselves good. I’ve written before about the measures GTA IV takes to help the player feel okay about the things she and her character do.

But these games go to great pains to make their protagonists endearing, or somehow sympathetic. There are plenty of videogames where you play quote/unquote bad guys, games like Grand Theft Auto, Saints Row, Manhunt, Prototype, Yakuza.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)